January 2025 Community Gathering: The Decelerator – One Year In

In January 2025, we were visited by our friends from The Decelerator, a ten-year initiative to support better endings and transitions in UK civil society.

It was only fitting that we close this “season” of the Composting and Hospicing community of practice the way it was closed the year before: with a visit from our friends at The Decelerator. Iona Lawrence and Louise Armstrong were important members of the Stewarding Loss project (from which this community also sprung!) and are the co-founders of The Decelerator, a ten-year initiative to help transform the experience and perception of closures in UK civil society.

It has only been a year since the organization formed, but they already had brilliant insights to share and a packed-out Zoom room that was hanging on Iona’s every word. Here are some of what they touched on:

Endings As Part of A Cycle of Change

As we’ve heard many times over the last few months — most notably in the December session with Sarah Weiler — nature gives us a wonderful basis to think about cycles of beginning, ending and regeneration, and The Decelerator’s work is rooted in this idea. iona noted that the group’s informal catchphrase is “We exist because endings are inevitable, but bad endings don’t have to be.”

To that end, they provide a free hotline for any one who is looking at a possible organizational or program ending, succession planning, structural transition, or merger and wants to do it well. For The Decelerator, better endings are those that “place an organization’s purpose at the heart of decision-making, take steps to treat everyone involved or affected by an ending with respect,

and ultimately they create the foundations for the renewal of civil society.”

The Power of Privacy

At the heart of the work are intimate, hour-long confidential calls in which people can share their concerns and fears about the major organizational changes they may be facing. The Decelerator currently has three “navigators” that take these calls, providing a “judgment-free” space to address both practical and emotional needs. Within the time of the calls — each individual is eligible for up to three free calls — the navigator brings the person into what they call a “mini deceleration” and offer a chance for the person on the other end of the line to breathe and take stock.

Not The Grim Reaper!

While many people who reach out to The Decelerator will indeed be having to close, this is by no means always the case. Oftentimes, callers may be thinking about leaving an organization and worried about how to erect the right sort of scaffolding to ensure their departure doesn’t have destabilizing effect. Other times people are just interested in safe space to talk about a topic that is often taboo and whispered in hushed tones.

Although, many people may wait until the house is falling before they call, The Decelerator also hopes that they can touch people further upstream and inspire more organizations to talk about endings earlier in their lifecycle.

Practicing the Principles

As The Decelerator works on supporting other organizations in thinking about their own longevity and impact, they are also thinking about what these ideas mean for their own project. Iona shared that one of the operating questions for the team is, “Can we escape some of the trappings of like survival or costs and growth as a measure of success in order to deliver our impact?” To that end,

If this leaves you clambering for more, I strongly suggest you check out their full report here. They also have dozens of hands-on resources on their website.

Thanks to Iona, Louise, and Sieske from The Decelerator for being such fantastic guests!

December 2024 with Sarah Weiler of Knowing When To Quit and The Quitting Quadrant

Sarah Weiler is a coach, a facilitator, a musician, a podcaster, and much more! She describes herself as a “carouseller”, or someone who is “all about honouring and focusing on the things that feel alive” for her. In December 2024, one of the things that made our community feel alive was being joined by Sarah to learn more about the fantastic work she is doing helping people think through frustration, persistence, quitting, and crafting all sorts of beautiful endings.

As usual, the 90-minute session positively flew by! Here are a few of the things that we discussed.

Endings and Emotion

Sarah began by discussing her earliest memories of quitting, dating back to her childhood. When the adults around her could see her, acknowledge her feelings, and affirm her decision to step away from an activity that was no longer serving her, it helped her develop a healthy attitude toward quitting. Oftentimes, we fail to realize that so much of the shame and negative emotion attached to quitting is rooted in what we were told and how adults pushed us too hard in our childhood. Healthy communication about closure can not start too early.

Look To The Leaves

Later on in life when Sarah was struggling about a decision to step away from a teaching role, she took a walk through a forested area to think. As she crunched through Highgate Woods on an autumn day, she thought about the dry leaves underfoot and how beautifully nature handles cycles of starting and ending. She took this as inspiration for how she might approach her personal challenge. As Sarah speaks — and sings! — about in her fanastic TEDx talk, the “leaves don’t ask permission to fall down”.

“Are you being honest with yourself about the things in your life? Because it’s quite likely that, as you evolve as a human. And as the world changes, that you are going to change what you need and what you want, so I think quitting is inevitable. So really, it’s like, how do we then love the process of quitting?”

The Quitting Quadrant

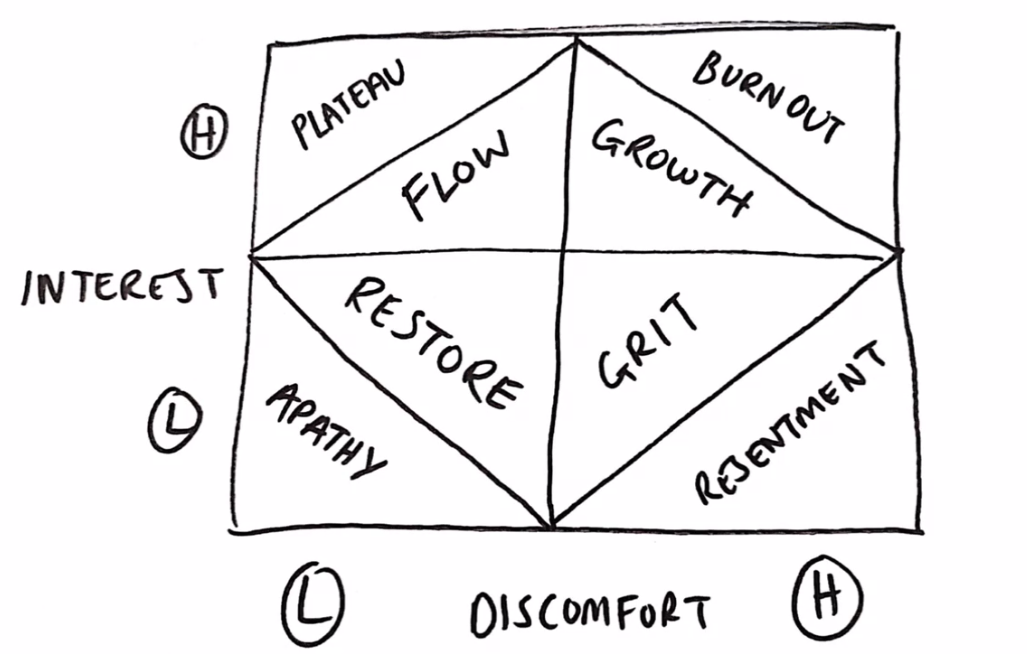

As part of her work as a coach and creator of the Knowing When To Quit podcast, Sarah spends a lot of time talking to people who’ve quit, are quitting, or considering quitting. This work eventually led her to create a tool called the Quitting Quadrant, which is a way of getting beyond the black and white thinking of “quit vs. stay”. She contends that finding the right fit in a work, project, or even relationship is a matter of continuously shifting interest and discomfort over time.

For example, if you are involved in something that you find very interesting, but it isn’t particularly enjoyable, you may burn out. In that case, you might need to explore how you can make it more fun. On the other hand, if you are participating in something uninteresting but easy, you might end up feeling apathetic and unengaged, which might just signal that you need to sniff around for something a bit more interesting or perhaps push yourself to get out of your comfort zone.

All that to say, that quitting is not a choice of last resort. It is on the table as an option. However, when we allow space of discernment around quitting or ending to be an invitation to ask ourselves some hard questions, we may discover there is a bigger menu to choose from!

November 2024 Community Gathering with Anna Shneiderman of BLACspace Cooperative

Anna Shneiderman was a co-founder of the Ragged Wing Ensemble, a theater company, and The Flight Deck, a cultural space in Oakland, CA. In 2020, after 17 years in operation, the group made the difficult decision to close. In this riveting session, Anna shared her experience with Ragged Wing and The Flight Deck and how she's carried out those learnings into new projects.

Her presentation was divided into 5 short acts:

Act One: The Beauty and The Struggle

In this act, we learned about the rise of the ensemble and the distinct challenges they faced running the group and managing their physical space.

Act Two: The Art of Leaving

We learned how Ragged Wing resolved that they had to shut down, and the appropriately creative approach they chose to take. During this section, attendees were invited to listen to some beautiful music Anna had created for the ensemble's final performance. While we listened, we were invited to answer prompts via text in the chat.

Act Three: Things Fall Apart

The ensemble's plan to close with one final performance was unexpectedly cut short by the arrival of COVID. Global political unrest coupled with internal strife and the inability to confront issues together in person only added to their difficulties. .

Act Four: Ritual Release

During this act, we learn how the group handled the nuts and bolts of dissolving the organization.

Act Five: Compost and New Sprouts

In this final act, we discovered what came after the end. In addition to the friendships that blossomed and grew during the life of the ensemble, many other things have sustained long past Ragged Wing’s final flight. The space has been taken over by a new community-based ensemble, and the work that Anna is doing with Oakland's BLACspace Cooperative as well as the support she has been able to extend to theater groups who have found themselves in similar straits is deeply infuenced by the lessons learned from Ragged Wing.

After Anna's presentation, a lively conversation continued in which we talked about the challenges of holding and owning physical space and remaining sustainable, the possibility of building internal mechanisms for closure, and the dangers of using the word "permanent"

Thanks again to Anna for joining us for another great session!

October 2024 Community Gathering with Catarina Moreno, serial interim executive director

In October we were pleased to welcome, Catarina Moreno as our guest. As a serial interim executive director and board member, she has found herself in the uncomfortable situation of having to shift into organization wind down after assessing that it is no longer a viable operation.

Here are some of the valuable insights she shared:

Financial Sustainability and People Sustainability

While it is well-known in the world of nonprofit endings that a lack of funds can quickly precipitate a closure, what is often less considered is the effect of having the wrong people in particular roles. Simply because someone is a founder or has been with the group a long time, it doesn’t mean they are best suited to the position. In some cases, these personnel issues might be so long-lasting that they have created a vicious spiral: you don’t have the right people in place to find the right people and you simply have to close.

Another angle on this that Catarina shared was related to knowing who you want to hire but not having the funds to make that a reality. In one of her closures, the team realized they needed more technical capability to realize their vision but they could not make the salaries that the kind of developers they wanted command. In this case, the project could not achieve its lofty goals and had to accept defeat.

Brainstorming With The Board

Because she is always brought in by the board, Catarina is keen to always keep the line of communication open with them, first and foremost. When she starts a new interim role, she does a thorough assessment of the organization to ensure that people, finances, processes, the market, and the overall landscape makes it a viable operation. In the case that she finds issues there, she is quick to bring them to the board.

Nonprofit leaders can often be afraid to come to the board with issues, fearing they will be misunderstood or penalized, but since Catarina is an interim, she finds she is not desperately clinging to the job, and is thus able to broach difficult topics. She highly recommends the board prompts in the “Closing The Doors” guide from The Power of Possibility for leading conversations on problem areas.

“I do see myself as ‘pre-fired’, because a sign of success for me is supporting a permanent leader to come in and set them up for success, but that also means that I oftentimes have a lot less emotional attachment to that role. I’m not the founder. I didn’t, you know, plan for this to be for the next 10 years. For me this is not super, super connected to every fiber of my being.”

— Catarina Moreno

A Wind Down Costs

In talking about the details of a shutdown, Catarina hastens to strongly recommend that organizations start the process early, making sure they are connecting with the right professional resources with an eye to ensuring there is enough money in the bank. She highlights the need to pay out costs like leases, severance, and professionals’ fees.

“It’s not cheap to wind down an organization. Even if you do a program transfer [to another organization], it definitely helps to have some seed funds available for them.”

— Catarina Moreno

She also stresses that while a merger or acquisition can sound good on paper, it usually ends up being a closure of a sort. True mergers in the nonprofit space are are increasingly rare these days and when one org absorbs another, it usually comes with the loss of branding and oftentimes many employees being made redundant. While some programmatic areas may be saved, the organization is rarely saved.

Finally, she made the point that money should likely be laid aside for a clean up staff person or staff people, bills that appear at the end, and any other requirements that may not have been anticipated but must be met to ensure good standing with the government. She advocates for keeping a prudent reserve to be certain things “end in a good way”.

September 2024 Community Gathering with The Endings Project

How do we plan for the ending of a project at the beginning?

We were graciously joined by Dr. Janelle Jenstad and Martin Holmes of the University of Victoria in British Columbia’s Humanities Computing and Media Center and their initiative The Endings Project. The Endings Project was initiated in 2015 to address the persistent and pernicious problem of precious academic work being lost in digital shuffles. The work grew out of the findings of Dr. Bethany Nowiskie’s Graceful Degradation Survey, in which she spoke to scholars about the ongoing maintenance of their scholarly work in digital form. Here are some of the themes that were touched upon in our gathering.

Complexity vs. Longevity

Martin has worked with the UVic humanities department for nearly years, so he was able to share a deep history of the department’s digital presence. In his presentation, he emphasized the ease with which he was still able to access websites from 30 years ago and highlighted the fact that there was no support burden. He rarely had to touch the websites that were constructed in HTML; whereas those sites built after the introduction of more sophisticated web frameworks would break often and sometimes couldn’t be supported by older web browsers. He also noted that without the ongoing maintenance, pages and sites could easily become security vulnerabilities for themselves and the larger system.

In addition to the technical challenges, complex technical systems work different to the way traditional paper publications work in academia. Versioning and links to references can be broken in an instant.

“So this Tamagotchi model that we adopted in the 2000s turns out to be really bad for developers like me because we spend our lives on maintenance. It’s bad for scholars, because their work seems to be untrustworthy and un-citable.”

The Digital-Analog Convergence

When considering how to archive projects for the long haul, books still have a lot to teach the digital preservation community. In addition to being constructed with durable materials, the best books, the books that survive put many copies in circulation in many different locations.

Janelle shared that at the same time that more complex frameworks were being introduced the scholarly community continued to make it clear that it did not take kindly to sources that changed constantly. The modern model of rolling updates is entirely ill-suited to the norms of academia. When a source changes too frequently, it begins to be regarded as something more akin to a wiki rather than a product that other scholarly work can build upon. In order to address this, the academic publishing world began to modernize the traditional convention of the edition to more closely model one common to the software world: the version.

“Books from the earliest days of the hand press period, which begins in 1475, probably will survive for hundreds more years, and they don’t require much to be operational other than our own eyes. So if books were like digital projects.

we wouldn’t be able to read a book from 1475, unless we still had a Gutenberg style handpress.”

Memento Mori

The Latin phrase memento mori means “remember that you are mortal”, and Janelle notes that this reminder is important in the space of digital building. Funding cycles end, interests change, and academics must turn their attention to other topics. The Endings Project helps academics start their digital documents with the end in mind. The Endings Project five principles provide a valuable checklist to ensure these projects are published “endings ready”. That said, the two insist that being ready for the end is a mindset and not a tool.

“In other words, we want our sites not to be Tamagotchis, but to be pet rocks ... If you lose interest and walk away for 3 years and come back. It’s still a pet rock. It still works exactly as it did before.”

August 2024 Community Gathering with Sarah Wambold and Rem Moore on Second (Digital) Loss

What if we could reimagine how we live, grieve, and die online?

Our August gathering was quite a bit more interactive and technical than previous ones, as our guests demonstrated a mockup of a tool that might be used to catalogue, store, and then slowly and gently degrade a digital artifact over time. Taking inspiration from their 2023 article, Only Loss, the two posited that technology might assist us to develop strategies to contend with, exert control over, and/or even prevent the “second loss” that occurs when we lose —- or lose access to —- the digital assets of deceased loved ones.

As practitioners in community organizing and digital research (Rem) as well as technical writing and funeral direction (Sarah), the two were able to draw from a variety of experiences and disciplines to engage the community in the technical demonstration, the question and answer session, and also a fantastic collaborative writing exercise. Here are a few salient themes that emerged during our conversation:

Loss Is Baked Into The Digital Experience

Rem and Sarah’s work was sparked in part by the question of how to deal with the lingering digital artifacts of those who have passed away. As a funeral director, Sarah was all too familiar with dealing with bereavement of the natural, biological sort but the long tail of digital recordings, images, writings was another matter. In exploring this question they turned to the work of Debra Basset, namely her article “Profit and Loss: The Mortality of the Digital Immortality Platforms” for language to think through the challenge of encountering and then losing precious digital remnants of those who have passed.

“Our state of being online right now is sort of a state of being bereaved. Whether we know it or not; whether we’ve experienced the ‘first loss’ or not. We’re kind of like always contending with it.”

Pushing Past Precious

According to Moore and Wambold, “Bassett makes a distinction between two types of encounters with the afterlives of data: intentional and accidental. Example data includes: photos, voicemails, texts, and posts that are scattered across devices and websites that we access throughout our everyday lives. Intentional encounters with this data are those where select data has been prepared in advance and curated to represent a particular memory of the person the data indexes. Accidental encounters on the other hand account for the refuse of data we leave behind unaccounted for, never intended to serve as memorials. Bassett interestingly frames these encounters through the prism of memory, referring to the data for each type of encounter as either ‘intentional digital memories’ (IDM) or ‘accidental digital memories’ (ADM). “ Moore and Wambold question the idea that memories can be digital and further raise the concern that the nature of the digital encounter can lead either to a drive towards the transformative — the desire to use the data in novel ways—- or towards the archival, something they refer to as “precious-making”.

in past sessions, particularly the one on museums with Erin, the group discussed the dangers of collective meaning-making through the hoarding of physical and digital items. Those of us who work with organizations grappling with what and how to preserve resources and create a digital legacy, must be aware of the tendency toward precious-making that could blind decision makers to the deleterious effects of merely archiving the work they’ve done in a form that makes it difficult to parse, engage with, use, or remix.

Capability Beyond “Keepability”

This session was particularly special for the level of engagement with the idea of composting and hospicing that underpins this community. The primary purpose of the demonstration was to challenge users to explore what it would mean for a chosen piece of data to no longer be recognizable and then to no longer be accessible. According to Moore, this provocative practice was in service of “getting past the idea that something that you have should be unchanging and offering ways for people to see what it would be like if that thing was to no longer exist.”

As we continue to grow this community, we hope to engage all sorts of practitioners in the collective imagination of objects, projects, organizations, and systems —- up to and including this community! —- fading away.

July 2024 Community Gathering with Naomi Hattaway of Leaving Well

Exploring graceful transitions at work.

Our group was fortunate to meet once again in July 2024, this time we were graced with guest Naomi Hattaway. Naomi works with organizations and individuals who are ready to design and carry out happier and healthier workplace transitions. Her Leaving Well framework offers tools and practices to guide and support her clients in creating team and executive departures that are smooth and generative for the individual and the organization.

Considering how intertwined staff departures can be with organizational endings, the conversation was lively and illuminating. Here is some of what we discussed.

Systemic Support Wanted For Endings And Transitions

Naomi began her short presentation by sharing a bit of her back story as well as her current focus on appealing to boards, foundations, and the greater philanthropic space to think more about the institutions and tools needed to support inevitable transitions in the nonprofit space. According to the most recent Boardsource Leading With Intent study, only 29% of nonprofits surveyed had a written succession plan. Further, only 27% surveyed felt they were prepared to handle an unexpected executive departure, and many board members expressed trepidation about leading through such a transition. Naomi emphasized the importance of boards in managing transitions of key staff and how disastrously things can go when boards find them self disastrously unprepared to manage the situation. For that reason, she advocates that executive teams —- rather than boards — take the lead on scoping the succession plan.

rom her vantage point, there is still a lot of work to be done to raise awareness and increase preparedness for endings.

“What’s most urgent for me is a transition from trying to support the individual, to asking the system to be responsible for endings and transitions.””

From Boardsource’s “Leading With Intent 2021” report

Talking About Endings Doesn’t Cause Endings

Another topic the group delved into is the perpetual fear individuals and organizations have about even speaking about endings. One member mentioned they pitched to do some facilitation for a nonprofit, but the when that group saw that the person specialized in endings they ran away fearing their community would think they were closing. Rather than using the engagement to think through what the end could (eventually!) look like them, they missed the opportunity for fear of contagion.

In Naomi’s case, she’s often found that when she approaches a board, the directors often push the discussion away offering things like, “Okay, that doesn't apply to us. We have a great person in charge. They're not going anywhere. In fact, we just gave them a raise.”

This all shows how far we still have to go to simply destigmatize conversations about endings.

Transition Personas

In Naomi’s view, “change is what happens to us, while transition is how we navigate through it.” As part of the work of supporting these transitions, Naomi sometimes has people on the team take a personality test so she can identify what role they can/might play in tackling the changes underway. In this way, people can have awareness about their own triggers and also know who to reach out to or task with things that might be overwhelming for them in the process.

Understanding themselves and their roles, helps everyone on the transition team move forward with a shared language, greater mutual understanding, and more confidence. The transition can, thus, be a chance not to “get back to normal”, but move forward as a more fortified institution.

The Power of “What If?”

Executive — and especially founder — departures don’t just mean possible tumult, they can also mean the complete topple of an organization. In addition to the personal reasons that might be pulling a key leader away from the organization, the overwhelming sense of responsibility to the nonprofit, the staff, the community, and the mission may cause absolutely paralyzing guilt, freezing the reluctant leader in place. In the work Naomi does with such individuals, she encourages them to lean into the thought exercise of “What if?” She pushes them to walk through what the consequences of leaving would be, what and who would be affected, and then move forward with a possible plan for mitigation.

Facing the mere possibility of leaving often proves to require more courage than actually leaving, but when we are brave enough to think through contingencies and design a plan, we can often leave behind a legacy free from the bleakest aspects of our fearful “what if” thoughts.

“Most of what I do is listen and sit almost by the bedside of folks that are navigating transition and navigating what ends look like.”

June 2024 Community Gathering with Erin Richardson of Frank and Glory

Who, what, and how long are museums for?

People in a well-kempt storage facility at a Smithsonian institution

This final Friday of June found us gathering again, this time with the fantastic Erin Richardson, PhD of the practice Frank & Glory, a museum services firm that supports diversity and sustainability in museum collections. Erin’s presentation kicked off with the stirring statement (borrowed from a former professor), “Everything is on a path to death.” With that cheery exclamation (!), we were launched into an extremely thought-provoking exploration of museums and archives and a lively Q + A. Here are a few topics we covered.

Conservation Is About Slowing The Time To Death

Erin began by walking us through some of the fundamentals of museums and museum management. For centuries, these institutions have been built to be both temples to the wealth and largesse of individuals, families, and institutions, while also serving as a means for us humans to tell a story about who and what we have been and what is and was important to us.

Mapping the fluctuation in the use of the term “permanent collection”

Since 2015, Erin has worked in art institutions helping them thing the policies that should govern what they hold on to, what should be disposed of, and how to think about growing their collections in the future. In that work, she has observed many spaces that were chronically over-filled and under-maintained, and this lead her to think more critically about how museums might imagine themselves while doing a better job of caring for people and planet. As such, the conversation was less focused on prescriptions and more on paradigm-shifting. She questioned what museums are for and what they should be for. She also questioned the “permanent collection” terminology so often used by museums.

“Not everything in a museum deserves to be there or was brought in by someone who knew what they were doing.”

Deaccessioning and Disposal

One of Erin’s areas of focus is deaccessioning. Deaccessioning is the process of moving an item from a museum’s collection. She also assists with disposal, which is the removal of the item (either by sale, destruction, or scrapping) from the institution’s facility. According to Erin, if the purpose of a museum’s collection is to support the institution’s mission in the present and into the future, then deaccession and disposal must be a continual process.

In addition to the challenges posed by a lack of space, maintaining aging items neatly and in a climate-appropriate way is not plausible for a great many museums. The cost of hiring expert staff and the upkeep of suitable facilities often proves too prohibitive — even for larger, better-endowed institutions — such that artifacts in “storage” often fall into decay or go missing in large disorganized heaps. And when so many of these items sit uncared for, they are often also unlabelled, uncatalogued, and unrecognized. The meaning-making work of museums often fails to extend to these forgotten items.

“Museums have so much stuff....holding on to everything would mean building football fields of climate-controlled storage.”

Memory and Museums

Erin also touched on the role that museums and monuments play in helping a society mark a traumatic events — the 9/11 Museum, Holocaust museums, war monuments —- they all serve as tributes to people that were felled in some of our nations’ darkest hours and epochs. That said, what events warrant museums and how long must those museums or monuments stand? Will people a hundred years from now be interested in learning about the events of September 11, 2001 and —-perhaps, more importantly —- will learning about those events help the people of the United States or the world in whatever will be important to those living in the year 2111?

A rendering of the proposed Pulse Memorial and Museum. The project was called off in 2023.

Our group also looked at recent US tragedies (e.g. the Tops supermarket shooting in Buffalo, NY and the massacre at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida) and wondered if there were, perhaps. other mechanisms for commemorating and honoring victims of heinous crimes that didn’t require the huge expense of erecting, staffing, and maintaining yet another building. Still others pushed back with the salient point that it seemed that the resistance to expanding the museum and creating new museums seemed to come right aat a historical moment when traditionally overlooked people —- black people, indigenous people, people in the LGBTQ+ community —- were demanding greater representation. For better or worse, the idea of the museum looms large in the imagination as something that can take an item in and signal to the world that it —- and the people connected to it —- once mattered.

If this sort of conversation sounds up your alley, please sign up to join us at an upcoming Community of Practice gathering.

May 2024 Community Gathering with Stopping As Success

Notes from our chat with members of the Stopping As Success: Locally-Led Transitions In Development Consortium

Michael, Grace, and the rest of the SAS+ team

This month we were joined by the fantastic Grace Boone and Michael Robinson from Stopping As Success: Locally Led Transitions in Development (SAS+) , which is a global consortium of organizations that were brought together by a common belief in local leadership. From 2017-2020, Stopping As Success developed case studies, tools, and partnerships to facilitate transitions to local leadership, and from 2021-2024, they (as SAS+) leveraged these tools to accompany a dozen of their partners in the hands-on process of transition. These accompaniments led to a refinement of the resources and tools that is presently in its final stages, as SAS+wraps up their publications and winds down operations to a close in April 2025..

On May 24, 2024, Michael and Grace joined a small and engaged group of CoP members to talk about their work and share some of their learnings. Read on to learn more about what we discussed!

The Importance of Incentives In Transitions

“International NGOs are not incentivized to transition.” Grace and Michael made this point at the beginning of the session and continued to return to it during the hour and a half gathering. An important aspect of their organization’s work has been to explore the push and pull factors that lead international non-governmental organizations and their local partners to embark on the transition path.

In their experience, transitions are usually initiated by the INGO in the midst o a politically-motivated funding shift. For example, USAID has se ta goal to transition 25% of their funded projects to local leadership by the end of 2025. As such, Stopping As Success (itself a USAID-funded project) has a keen focus on guiding INGOs towards the most responsible ways to empower their local teams to step up to the challenge of taking over local offices or spinning out initiatives into their own entities. As Michael stated, “Power is so essential to these conversations.” By which he means, who has it and how can SAS —- and other likeminded organizations —- prod them to release it to those who are closest to the problem? As we continue to see foundations grapple with the same questions, the conversation is a timely one with broad relevance throughout civic society.

Transitions Require Shared Language

Though many of their resources emphasize the importance of “responsible transitions”, Michael and Grace were quick to highlight the importance of making sure everyone was on the same page about what terms like “responsible” “transition” even mean, To that end they provide a transition plan template to help all parties come to the table. The planning effort helps all parties craft a bespoke and appropriate vision for what their own shift from INGO to local power will look like and how they can do their best to honor each other and themselves in the process. As Grace noted, “People have different definitions of transition .How do you contextualize this and get buy-in? And how can the transition process move beyond just a discreet project aim?”

In some cases, INGO-funded projects have developed enough of a presence on the ground to feel a sense of readiness to go it alone. They point to Talking Drum Studio as one such example. As a highly-visible producer of innovative radio and television programs in the former conflict zones of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Nigeria, TDS had much more name-recognition than the INGO that it had emerged from (MIchael’s organization Search For Common Ground.) So when time came for it to transition to operating independently, they knew that their name held valuable cache’ that would enable them to pursue the sort of of funding and relationships that would help them land on their feet. However, In other cases, local teams may have less of a sense of what they will need to do or be in order to manager their own affairs. The prospect of life without the expertise and connections provided by the prominent and well-funded INGO, can elicit quite a bit of trepidation!

In the face of such concern, SAS stresses the importance not only of transition planning and visioning, but also capacity-strengthening. Capacity strengthening (also known as capacity building or capacity development) is a term used throughout the INGO world to describe the work of enabling people and groups to successfully handle their own affairs. In the case of transitions from international to local, capacity strengthening may mean learning how to manage budgets, developing fundraising skills, fostering new partnerships, or developing a staffing plan. However, what remains most important is for the local group to define its own vision of the potential new local organization and feel confident stepping into leadership.

“People have different definitions of transition. How do you contextualize this and get buy-in? And how can the transition process move beyond just a discreet project aim?”

Capacity-Strengthening Is Omnidirectional

SAS hastens to state that their vision of capacity strengthening is rooted in reimagining the INGO to local organization dynamic. As Michael emphasizes, “Capacity strengthening can be very ineffective as a one-way street.” As such, they prescribe a process of mutual capacity strengthening, in which all parties bring their unique abilities and knowledges to the table. While the INGO can help the local organizers navigate the wilds of the NGO world, the local groups always have much to share about how and where the work is down and what can be down better/more effectively. For example, as part of the staged transfer process from INGO Nuru International Nuru Kenya, the Kenyan team was able to provide feedback to the international organization about how the transition was going and what changes they’d like to see moving forward.

In addition, shifts in power and ownership can also benefit from local-to-local capacity building work. Such was the case when Talking Drum Studio Liberia reached out to BRIDGE, a Georgian organization that had spun out of INGO Oxfam. Peer to peer learning can be a critical — and critically non-hierarchical!— way for knowledge and skills to be share.

The Transition Space Still Needs Endings

As a community of practice focused on hospicing and endings, we (of course!) had to ask how Stopping As Success views successful closures. The sad news was that they unfortunately didn’t delve into cases where local groups chose to close down operations rather than continue operations as a stand-alone entity. The good news is that Michael and Grace are keen to keep joining our gatherings and exploring how they can apply what is being shared to a broader understanding of how to foster mutual success even when operations shut down.

Thanks again to Michael and Grace for joining us for another wonderful session! You can check out the calendar for upcoming CoP gatherings here.

April 2024 Community Gathering with Geoff Revell of WaterSHED

In which we relaunched the community and had a lively discussion of planned exits, fostering local leaderships, and the power of confetti canons!

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

The Community of Practice was relaunched in earnest on 26 April 2024 as a small group of us gathered to listen to what our guest Geoff Revell of closed NGO WaterSHED had to share about his experience of crafting and executing a intentional organization sunset/exit to community. We used his excellent 2021 article, “Exit Strategies”, from Stanford Social Innovation Review as a starting point for our wide-ranging discussion.

Here are some of the major takeaways:

Begin With The End In Mind

Geoff talked about how “So, who is gonna do this after we are gone?” became a constant mantra amongst his team. Everyone that worked for WaterSHED was hired and onboarded with the understanding that they would end after the allotted time and he found that the project attracted people who liked the idea that there was a planned exit. He also took great pains to stress how having a planned sunset encouraged efficiency and economy in action. “Thinking with the end in mind is a great device to get people to focus on the things that matter.”

In addition, the company boldly promoted their exit to donors and partners years ahead of time. The Strategic Exit page was added to their website quite early on so their intention to exit was made plain.

“Thinking with the end in mind is a great device to get people to focus on the things that matter.”

Exiting To Community Can Happen Piece By Piece

Before making the decision to close, nonprofits will often look around for stakeholders to take over, this can frequently take the form of an exit to community process. However, too often the idea is that someone(s) else will take over the organization whole-cloth — keeping the name and activities relatively unaltered. In contrast, WaterSHED’s approach was to turn over different programmatic areas to interested and capable parties. Their ten-year time horizon for closure meant they had ample time to find people who were keen to take over the work, and WaterSHED could also be a partner to those interested parties in the cases where capacity-building was required.

Although funders often pay lip service to the idea of initiatives being locally-led (see, for example, USAID’s locally-led indicator agenda), global “development” projects often remain stubbornly foreign-run while creating a class of people in the global south who become quite used to the enticing per diems and other employment opportunities that the foreign NGOs offer. It was this type of regime, that caused WaterSHED to draw the ire of some local authorities. Unlike other groups, they refused to create local reliance on them continuing to funnel foreign money into Cambodia. They, instead, encouraged locals to take over the projects that they found valuable to the community.

Although, some potential partners struggled with the unorthodox manner in which WaterSHED carried out its activities, many of the locals that eventually stepped up to the challenge took it on as a source of pride in local, Cambodian self-determination.

Geoff shared with us how the local groups brought in true pomp with the handover ceremonies, with the events featuring awards, medals, and even confetti canons! The pageantry of the transitions helped draw more local people to the work.

People Often Assume Closure Is Chaotic and Painful

Despite WaterSHED’s continued insistence that the plan was always to close, the staff continually ran up against the assumption that something had gone wrong, most notably that they had run out of money. Hearing this, the community members at our gathering agreed that there was need to shed more light on closures — particularly well thought-out, intentional closures — so that funders, governments, communities, and even fellow-NGOs would have some points of reference. When more people understand that endings can be planned and a mark of success —- Geoff used the term “badge of honor” — there are more hands on deck to ensure the ending goes well.

Thanks again to Geoff for joining us for a rousing session! You can check out the calendar for upcoming CoP gatherings here.